Facilitating writing retreats is a bit like being a yoga teacher. I was remembered this at my last retreat. At the end of our first day, one participant said “I feel tired, but in a good way, like after a great yoga class.” Which is all you could hope for. But Like yoga teachers, writing retreat facilitators need energy from someone more experienced. You need to keep learning.

Luckily, I was half way through Rowena Murray’s rhetoric course.

Rhetoric is a triangle

What is rhetoric? It is “the art of making the best possible case” (Fahnestock, 2011: 158), or writing with “a sense of audience and purpose” (Flower & Hayes, 1980: 21–32). Rhetoric links all three sides of a triangle: writer, audience, and purpose. When the triangle aligns, the audience sees your point – whether they agree or not!

On this two-day course, we tested rhetorical techniques and used them to make a case in writing:

- Audience analysis

- Rhetorical modes of exposition and argument

- Structuring and writing styles

As we started, I remembered what my A level history teacher used to write on the side of my essays: “Why are you telling me this?”

Modes of exposition

On day one, we examined all seven rhetorical modes of exposition:

- Description

- Narration

- Process

- Comparison & contrast

- Analysis

- Classification

- Definition

Once we had the theory, we got straight into drafting texts to use in practice. We had questions to keep us on track, and feedback criteria to see if we hit that target. I realised, yet again, that I can happily write a thousand words in less than an hour – talking to my audience. But then I need to restructure to boil it down to my main point. I have to remember the purpose side of that triangle.

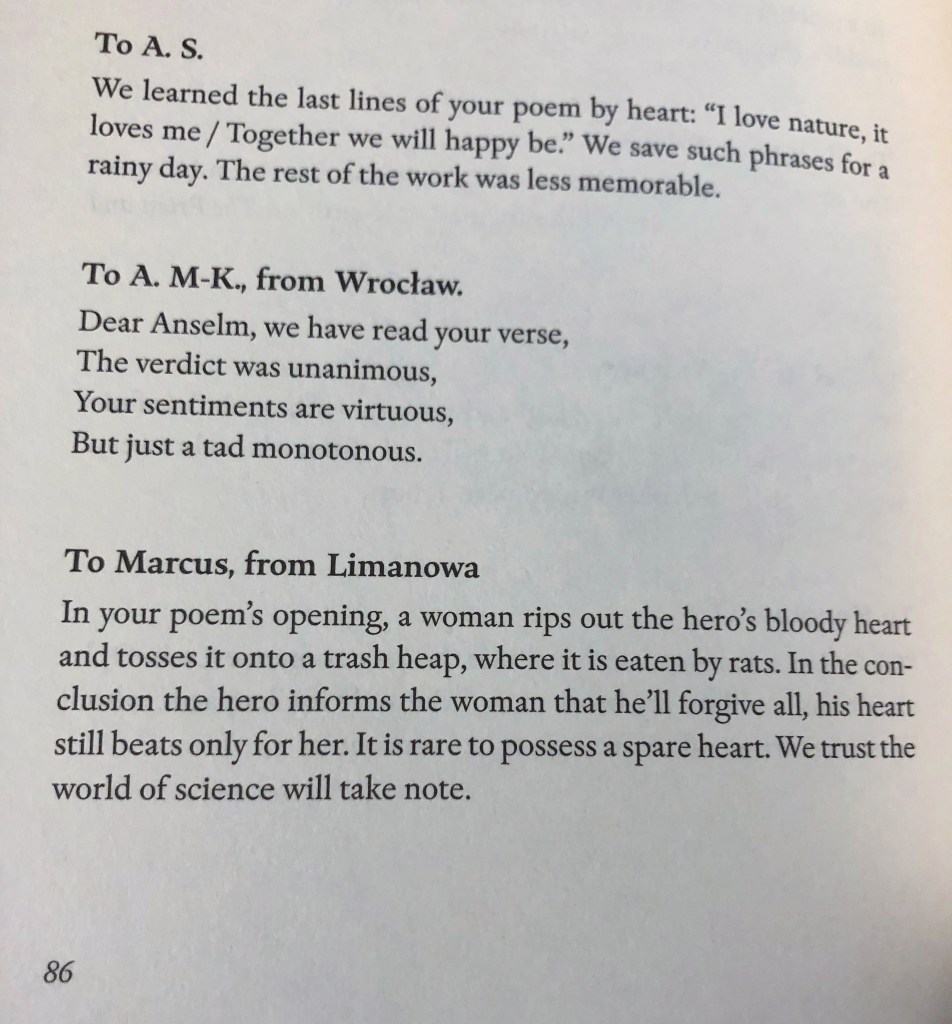

Rowena Murray shows you all these modes of exposition in the Journal of Academic Development and Education, in her editorial on Snack and Binge Writing. I tried using them all here – but I didn’t use them in order, or label them. Can you spot all seven? Would a different order have worked better?

Modes of argument

On day two of the course, we tested the rhetorical modes of argument:

- Evaluation

- Causal analysis

- Refutation

- Proposal

Even after one day, I noticed a big change in how I used my writing time. The second time we had an hour to practice one mode, I wrote 500 words instead of a thousand. But it was much better structured. I was much more focused on proving my point.

Some modes of argument and writing styles felt like old friends but on the course, I thought about them in a new way. For instance:

When you write a proposal, it should have an hourglass shape, that begins with the issue up for debate, definitions, and causes.

The proposal statement is the middle

The proposal ends with the supporting arguments and solutions. Not many people use hourglasses these days, but you might still use an egg-timer (for snack writing), which is the same shape. You could look at how George Herbert does it in his beloved poem and call this a proposal with wings.

Structuring your argument

My key takeaway from this course was: spend more time planning than writing. Were you taught to spend the first 10 minutes planning your answer to an exam question, and use the rest of the hour to write it? I was. But what if you turned that on its head? Liane Reif-Lehrer suggests you spend 60% of your writing time outlining, 10% turning it into prose, and 30% revising. Or even 90% planning, so you need very little time to write and revise.

You can plan an article down to 100-word blocks, by dividing it into sections, subsections, and sub-subsections. Then you know exactly how much space you have for every stage in your argument. Which is especially useful if you are co-authoring. Once you have your outline, you only have to write a hundred words at a time. That should be easy to fit in – with an egg-timer, an hourglass, or wings – however busy you are.

Rhetoric on writing retreat

Rowena’s course moved the theory of rhetoric into writing practices that you can remember and use. I found it useful to adapt the rhetorical modes to writing retreat contexts. You, the writer, can focus before you start by filling the other two sides of the rhetoric triangle:

For purpose, one easy technique is to think of a verb. What am I doing in this section or session? Is my aim to argue, claim, analyse, confirm, dispute, reveal?

For audience, build up a mini reader avatar using wh-questions. Who is going to read this? When? What do they know about my topic? Where will they agree – and disagree? Why? How can I make them see it in a new way?

And the key, as ever, is to set specific goals. How long have you got? In that time, how many words can you write?

Zooming ahead

We did this over Zoom, using breakout rooms to share our practice texts. We met on two successive Tuesdays from ten till two. Four hours at a stretch online sounds like a lot, but we moved between big group and small groups, listening and talking, reading and writing. With proper breaks. So the time flew past, but we covered a huge amount. Just like on a writing retreat.

Of course, in person we could have had more social time and focus. But online was more accessible. Besides me in Finland, writers came from all over the UK, at all stages of their academic careers. Some even attended while in covid isolation. Sharing your writing on-screen is scary, but in a breakout room with two or three others, it is doable. It helps. A lot.

Take this course!

Rowena Murray’s retreats and training always bring you back to the writing. Even though this was a taught course, I got a lot written. I restarted an article that I’d left to sit, because I was stuck on the analysis. Now I know how to tackle it. And I learned some new criteria to focus my writing on my audience and purpose.

Have I convinced you to take the course yourself? You tell me!

new retreat dates – seuraavat retriitit